By Helena Smith in Athens | Sun 3 May 2015 21.37 CEST

As Syriza nears its 100th day in office, Alexis Tsipras walks a fine line between eurozone compromise and being accused of submitting to Angela Merkel

In the countdown to Syriza marking 100 days in office, Greece got its first crisis monument. Arms outstretched, mouth wide open, his face locked in despair, the sculpture depicts a man dangling from a financial index in free fall. Below, his world of concrete and stone lies broken and smashed.

Officially known as the “crisis work”, the art piece has attracted a steady flow of spectators to the place where it has been erected, in the shadow of a bridge on the boulevard that connects Athens to the sea. Flowers lie next to it as if in mourning for all that has passed.

For Tasos Nyfadopoulos, the young sculptor behind the work, it is the first public tribute to the thousands of suicides the crisis has left in its wake. And an expression of everything Greeks have come to feel. “People want art to express them,” he said. “And with this work I tried to express my own feelings and let society at large speak.”

On the rollercoaster ride that is the debt-stricken country’s epic battle to stay afloat, many had hoped that Syriza would also provide solace. But five years after Athens was forced to be bailed out by the European Union and International Monetary Fund (IMF) – accepting the biggest rescue package in global financial history – Greeks are not sure what to think. What they do know is that after five years of dancing to the tune of austerity – of making the sacrifices necessary to keep bankruptcy at bay – they are, like Nyfadopoulos’s dangling man, once again staring in to the abyss.

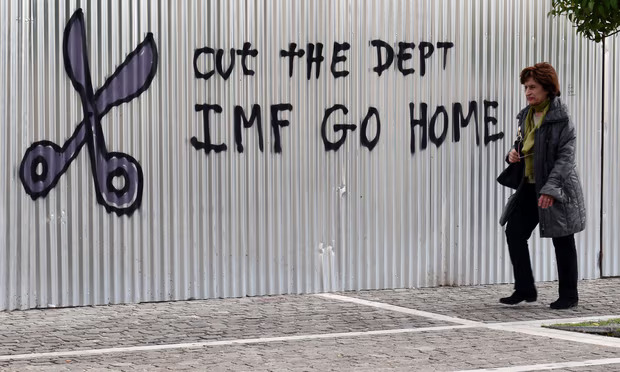

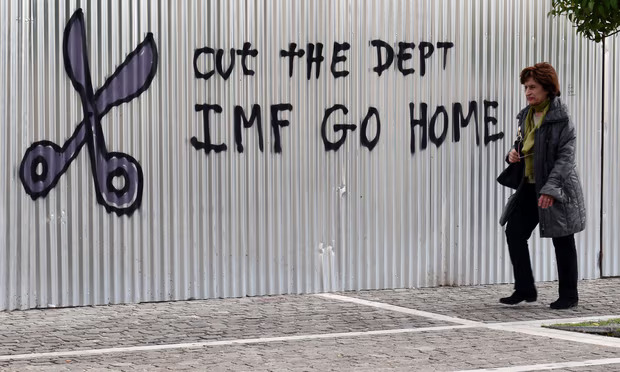

A woman walks past a slogan in central Athens in January. The great wave of hope that had brought Syriza to power has now crashed on the rocks of renewed uncertainty. Photograph: Louisa Gouliamaki/AFP/Getty Images

The great wave of hope that had brought the radical leftists to power – on a promise to cancel austerity – has crashed on the rocks of renewed uncertainty over whether the country can stay the course of eurozone membership at all. More than ever, Greece seems headed for the exit door.

“It is very hard to give Syriza a good score in anything other than good intentions,” said Aliki Mouriki at the National Centre for Social Research. “Their interest may be to put people first, before the banks, but their handling of negotiations has been a mess and their tenure very disappointing.”

Figures would appear to support that sentiment. Following three months of fruitless talks to reach a cash-for-reform deal with creditors, public finances have never been worse. In an atmosphere of fear, the real economy has come to a grinding halt. Disquiet over whether prime minister Alexis Tsipras’s leftist-led coalition can keep up with state expenditure and meet debt repayment obligations – it must pay nearly €1bn to the IMF by 12 May – has added to the mood of mounting angst.

With each make-or-break deadline comes a sliding scale of drama and intensity. Will the country defy the doomsayers and unlock the €7.2bn in held-up bailout funds it so desperately requires? Or will it slip inexorably into the unchartered waters of default and economic catastrophe? Last week, in a glimpse of what the future might bring, elderly Athenians stood for hours outside banks as the government struggled to pay pensions.

People receive olives and bread distributed for free by municipality of Athens in February. After three months of fruitless talks, Greek public finances have never been worse. Photograph: Yannis Kolesidis /EPA

“We are not at the point of outright panic yet but people are clearly very worried,” said Mouriki, a sociologist. “Close to €30bn has been withdrawn by depositors and firms from bank accounts since December which is more that at the height of the crisis in mid 2012.”

But shades of panic have arrived and, indelibly, have begun to reveal themselves in other ways: from the government sequestering the funds of public bodies to help pay bills; to Greek borrowing costs soaring on fears of insolvency; to savers stuffing their freezers with cash and ever more parents encouraging their children to move abroad. “I have come round to accepting that my daughter’s generation is a lost generation,” lamented Panaghiota Mourtidou, sitting in the food pantry she helps run in central Athens. “At 30 there is no chance that she will have any of the certainties that we enjoyed but maybe my grandchildren will. That, now, is my great hope.”

It is testimony to the Greeks’ enduring faith in hope that Syriza is still leading in the polls even if support for its negotiating strategy has plummeted and diehards speak of crushing concessions being made.

The party, on the margins of politics barely three years ago, was shown in a poll released by polling agency Marc three days ago to be 14.8 points ahead of the conservative main opposition New Democracy. Backing for Yanis Varoufakis, the controversial finance minister most associated with the reckless brinkmanship that has alienated Athens from its euro-area partners, is also high. Reports of his being rounded on by eurozone counterparts decrying his “amateurish” ways at a summit meeting on 24 April, appear only to have rallied support. The flamboyant politician – since relocated to the less visible post of supervising political negotiations – was mobbed by sympathisers at a May Day march with many cheering his vocal anti-austerity views.

Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis talks with a protester in a demonstration during a May Day rally. He continues to enjoy widespread support, despite a lack of progress from Syriza. Photograph: Alexandros Vlachos /EPA

“His style may be a little odd but he is a good economist. That they had him in a room and insulted him for three hours is absolutely unacceptable,” said Stamatis Vassilaros, a doctor echoing a common refrain. “What has become clear is that under no circumstances do they [Europe’s rightwing governments] want Syriza to succeed. Success would mean the beginning of the end of these gentlemen who have forgotten what democracy means and the principles upon which a united Europe was founded.”

But while defiance is in the air, so is anger over the hardship that austerity has also wrought. Far from bridging the gap between Greece and its partners, the medicine meted out by international creditors has exacerbated the country’s decline. Unemployment was meant to have peaked at 15% in 2012; it now stands at nearly double that with more than 50% of young Greeks out of work.

The charismatic Tsipras may have confronted growing impatience abroad but at home he is able to draw on the discontent unleashed by policies that have failed to deliver the promised results. And with each passing day the situation only gets worse with growing reports of privation outside Athens.

On Aegina, the island that served as the nation’s first capital shortly after its war of independence from Ottoman rule, poverty has increased noticeably in the past six months. “We’ve had to start saying no,” sighed Athina Pirounakis, whose charity, Aegina Volunteers, distributes food and clothes to the needy. “We began with 80 families and now have 170, and every day there are requests from more,” she said. “We are talking about people who, literally, cannot afford to put food on the table.”

Scuffles broke out between police and protestors during May Day demonstrations in Athens. Syriza remains ahead of New Democracy in opinion polls, but discontent is growing among Greeks who voted them to power. Photograph: Nikolas Georgiou/Zuma Press/Corbis

In the neo-classical town hall on the isle’s picturesque seafront, Dimitris Mourtzis, the local mayor, reckons that living standards have dropped by 35% since the crisis erupted. “Everything is in ruins,” he says shaking his head ruefully. “Greeks aren’t to blame. Across the board our politicians’ behaviour was despicable. We had countless EU-funded development programmes to prepare us for our entry to Europe and where did the money go? Not into development, that’s for sure. It went into buying politicians’ votes.”

Aegina, which lies 16 miles southwest of Athens and is where Nikos Kazantzakis wrote Zorba the Greek, ironically is also where leading government members, including Varoufakis, have second homes. As in other islands, tourism will be a life saver in the coming months. “But,” says the mayor, “there are so many problems. And the big question is not what they have done but what they will do after the first 100 days.”

For Tsipras, the youngest leader to hold high office in modern times, what lies ahead is a litany of choices with potentially explosive effect. To date the politician – one of Greece’s canniest operators – has managed to maintain approval ratings of close to 70% despite rolling back on almost every promise he has made. Angela Merkel, the German chancellor and architect of the austerity he has vowed to defeat, has become a regular interlocutor.

Now, as the day of reckoning approaches, he will have to decide whether to placate foreign lenders by agreeing to the terms of another rescue programme – conditions that though painful will keep Greece in the single currency – or jettison the hardliners in his own party. Militants led by energy minister Panagiotis Lafazanis say any rupture with Europe would be better than signing up to an accord that crossed Syriza’s myriad red lines. Ominously, Golden Dawn, the neo-Nazi party and the country’s third biggest political force, have accused Tsipras of submitting to Merkel.

Golden Dawn supporters hold the party flag and Greek national flags during a rally in Athens last year. The neo-Nazi party is Greece’s third biggest political force, and has accused Tsipras of submitting to Merkel. Photograph: Losmi Chobi /Sipa/Rex

“This is an historic moment,” says Anna Asimakopoulou, a shadow finance minister for New Democracy. “If the wrong choice is made it will change the course of history for Greece and for several generations the Greeks might be living in a different reality to the one they know.”

In recent weeks the rhetoric has reached boiling point in parliament. “It’s at gutter level,” said the straight-talking MP, a Greek American raised in New York. “Tsipras is going to have to take a good look in the mirror and decide who he is. Either he leaves behind his entire left, pro-drachma people or we leave the euro.”

Analysts are in no doubt that the choice will be as definitive for the self-styled leader of Europe’s anti-austerity movement, as the destiny of Greece itself. And perhaps because of this he has raised the spectre of putting any deal that might be reached before the Greek people for approval. The prospect – one that would bring the crisis full circle three years after George Papandreou also proposed holding a referendum – has been quick to send tremors through Europe. Sensing further instability, the vast majority of Greeks – led by the business sector – have urged the government to compromise, according to polls.

“Tsipras got into power on the votes of the old centre left and that is where he has to move,” says Christos Memis, a veteran political commentator now in charge of the respected news portal Protagon.gr. “If he doesn’t want to lose his allure and go down as the man who oversaw euro exit, it is his only option.”

The battle lines are being drawn – in and outside Greece. And while time is of the essence, there are no guarantees.